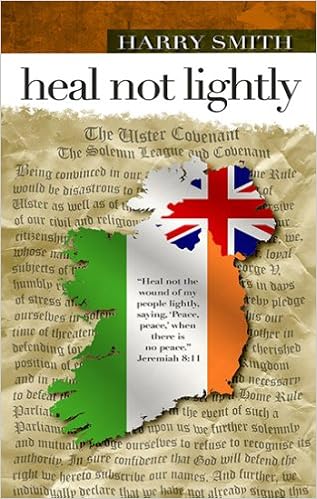

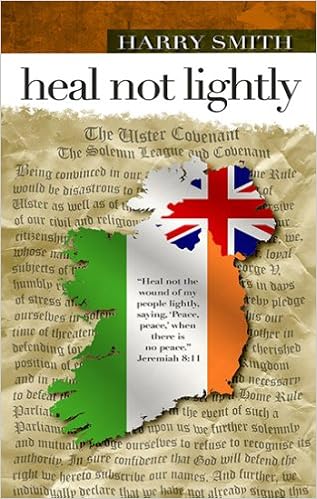

Subtitled:

Deep Healing Needed

HEAL NOT LIGHTLY, as the title suggests, is a book about healing – not

light healing that might be applied with antiseptic cream, or a

sticky-plaster or band-aid, but a deep one, that might require the skill

of a surgeon. More often than not, problems between ethnic groups fit

into the latter category. This book takes a look under the surface of

what have been called “The Troubles” of Northern Ireland, and Harry

Smith finds a few areas requiring the deeper sort of healing.

One

of these is the Ulster Covenant, which was the response of the

Protestants of Northern Ireland in 1912 to the proposed Home Rule Bill

that had been submitted to the British Parliament, and looked like was

going to become law. This would have placed all of Ireland, North and

South, under an autonomous parliament in Dublin.

This was good

news to the Irish Catholic community, whose experience of British rule

had been quite turbulent and often traumatic. However, the Protestants

community in Ireland didn't share the same historical perspective. There

were other issues.

Among the biggest was that such a parliament

would have a Catholic majority. The Protestant community who had

migrated to Ireland in large numbers during the times of Queen Elizabeth

I, James I, and William of Orange to serve as their political pawns,

would suddenly find themselves in the minority. It was rightly believed

that the Dublin government would be heavily influenced by the Catholic

Church. A common slogan was, “Home rule is Rome rule”. If that seems

far-fetched, remember that religious freedom was not taken for granted

in Europe then as it is now. Also, those were the days before the

Vatican II council, which liberalised the Catholic Church's position

towards non-Catholics (however, even now, there are many Protestants who

regard these changes as strictly cosmetic).

So, many Protestants

feared the worst. The Protestants of Northern Ireland, primarily under

the leadership of the Presbyterian, Church of Ireland and the Methodist

churches, banded together and signed a document called the Ulster

Covenant. In this, they swore not to submit to Home Rule, and in the

event that it was forced on them, to resist, taking up arms if

necessary. Some prominent Ulster Protestants signed it with their blood.

This covenant has been the basis of Northern Irish identity ever since.

The

first chapter of the book contains numerous statements in the press by

various church leaders, politicians, editors and others regarding the

danger that was eminent, and the necessity of every Protestant who

values his history and his freedom as a British subject. Just reading

them gives one a sense of the atmosphere that prevailed. In all, around

250,000 men signed the covenant – with a similar number of women signing

a supporting document.

Harry Smith also goes into some more

background, relating how former Moderators of the Presbyterian Church in

Ireland utilised the Scottish National Covenant of 1638 to unite people

politically and spiritually against the Home Rule Bill.

The

Scottish National Covenant was a vow of solidarity, which established

Scotland as a Christian nation under God with their Presbyterian values,

in their resistance to attempts at control by the Church of England. In

effect, it was a reminder to God whose side He was on. It was even said

that in the same way that God had once regarded the Israelites as His

chosen people, whom He had now rejected under the New Covenant, He now

regarded the Scottish nation. In other words, Supersessionism, or

Replacement Theology was a cornerstone of Covenant terminology.

Then,

we read details of how, during the times of James I and William of

Orange, Scottish Protestants were offered land in Ireland from which

Irish Catholics had been forcibly removed. They regarded this as their

divine mandate, and that later became the basis of the Ulster Covenant.

So,

whose side was God on? Reading all the press statements in the first

chapter compels one to consider that a covenant may have seemed like a

good idea at the time. In fact, one would have been considered a traitor

– an enemy of God – for opposing it. But was it really a good idea? The

song by Bob Dylan, “With God on Our Side” comes to mind.

Harry Smith believes that the Ulster Covenant is now one of the biggest hindrance to peace in Northern Ireland.

But,

you ask, didn't the Good Friday Agreement bring peace? There still

exist huge fences crossing whole sections of Belfast, which are referred

to as the “peace wall”. They are, in fact, proof that there isn't

peace, otherwise, why would we need walls to separate us? That actually

fits with the same passage in Jeremiah 8:11 from which Harry Smith took

the title: "They have healed the wound of my people lightly, saying,

‘Peace, peace,’ when there is no peace."

God showed Harry Smith

that it is like a log-jam that holds back the flow of His Spirit - like

the river mentioned in Ezekiel chapter 47, which brought healing to the

land. Repentance at Church government and personal levels are essential

for the removal of this log-jam so as to release the river of God.

To

achieve peace in Northern Ireland, Protestants in Northern Ireland must

renounce the Ulster Covenant, and the Nationalist community must

renounce the Sinn Fein Covenant (that was signed a few years later); let

go of our political agendas, and trust God to direct the future

according to His plan.

There are also chapters on intercessory

prayer, a helpful exposition on the basis for believers' authority, and

many practical guidelines on how to seek God's plan for a city or a

nation, with particular emphasis on Ireland. Even if it were just for

those aspects, it's a worthwhile read.

If you're interested in

ethnic reconciliation and want to understand more clearly, what you're

up against, definitely, get this book.